Book of Leviticus利未記書

| Tanakh and Old Testament | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

|

||

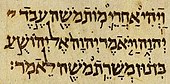

The Book of Leviticus (from Greek Λευιτικός, Leuitikos, meaning "relating to the Levites"; Hebrew: ויקרא, Vayikra/Wayikra, "And He called") is the third book of the Hebrew Bible, and the third of five books of the Torah (or Pentateuch). The English name is from the Latin Leviticus, taken in turn from Greek and a reference to the Levites, the tribe from whom the priests were drawn. In addition to instructions for those priests, it also addresses the role and duties of the laity.[1]

Leviticus rests in two crucial beliefs: the first, that the world was created "very good" and retains the capacity to achieve that state although it is vulnerable to sin and defilement; the second, that the faithful enactment of ritual makes God's presence available, while ignoring or breaching it compromises the harmony between God and the world.[2]

The traditional view is that Leviticus was compiled by Moses, or that the material in it goes back to his time, but internal clues suggest that it originated in post-exilic (i.e., after c.538 BCE) Jewish worship centred on reading or preaching.[3][4] Scholars are practically unanimous that the book had a long period of growth, that it includes some material of considerable antiquity, and that it reached its present form in the Persian period (538–332 BCE).[5]

利未記書

| 塔納赫和舊約 | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

|

||

在利未記的書(從希臘 Λευιτικός,Leuitikos,意思是“與利未人 “; 希伯來語:ויקרא,Vayikra / Wayikra “,他稱之為”)是第三本書的希伯來文聖經,和五本書的第三在托拉(或摩西五經)。的英文名字是從拉丁文利未記,依次從希臘和參考取利未人,從他們的祭司們繪製的部落。除了 那些祭司的指示,這也解決了角色和職責俗人。[ 1 ]

利未記掌握在兩個關鍵的信念:第一,世界是創造了“非常好”,並保留對實現這一狀態雖然它很容易受到容量罪和污穢,第二,是儀式的忠實頒布,使神的存在可用,而忽視或違反它損害上帝和世界之間的和諧。[ 2 ]

傳統的觀點認為,利未記是摩西所編譯,或者在它的物質可以追溯到他的時間,但內部的線索表明,它起源於被擄後(即後c.538 BCE)猶太人的崇拜集中在閱讀或說教。[ 3 ] [ 4 ]學者們幾乎一致認為這本書有增長的長週期,它包括相當古老的一些素材,而且它在達到其目前的形式波斯時期(公元前538-332)。[ 5 ]

Structure[edit]

(See Gordon Wenham, "The Book of Leviticus", and Frank Gorman, "Divine presence and community")[6][7]

I. Laws on sacrifice (1:1–7:38)

- A. Instructions for the laity on bringing offerings (1:1–6:7)

- 1–5. The types of offering: burnt, cereal, peace, purification, reparation (or sin) offerings (ch. 1–5)

- B. Instructions for the priests (6:1–7:38)

- 1–6. The various offerings, with the addition of the priests' cereal offering (6:1–7:36)

- 7. Summary (7:37–38)

II. Institution of the priesthood (8:1–10:20)

- A. Ordination of Aaron and his sons (ch. 8)

- B. Aaron makes the first sacrifices (ch. 9)

- C. Judgement on Nadab and Abihu (ch. 10)

III. Uncleanliness and its treatment (11:1–16:24)

- A. Unclean animals (ch. 11)

- B. Uncleanliness caused by childbirth (ch. 12)

- C. Unclean diseases (ch. 13)

- D. Cleansing of diseases (ch. 14)

- E. Unclean discharges (ch. 15)

- F. Purification of the tabernacle from uncleanliness (ch. 16)

IV. Prescriptions for practical holiness (the Holiness Code (chs. 17–26)

- A. Sacrifice and food (ch. 17)

- B. Sexual behaviour (ch. 18)

- C. Neighbourliness (ch.19)

- D. Grave crimes (ch. 20)

- E. Rules for priests (ch. 21)

- F. Rules for eating sacrifices (ch. 22)

- G. Festivals (ch.23)

- H. Rules for the tabernacle (ch. 24:1–9)

- I. Blasphemy (ch. 24:10–23)

- J. Sabbatical and Jubilee years (ch. 25)

- K. Exhortation to obey the law: blessing and curse (ch. 26)

V. Redemption of votive gifts (ch. 27)

結構[ 編輯]

(見戈登·溫漢姆,“利未記”,和弗蘭克戈爾曼,“神的存在和社區”)[ 6 ] [ 7 ]

在犧牲一,法律(1:1-7:38)

- 對於在帶來產品的俗人A.指令(1:1-6:7)

- 1-5。燒,穀物,和平,淨化,賠償(或罪惡)產品(章1-5):產品的類型

- B.說明祭司(6:1-7:38)

- 1-6。不同的產品,並增加了祭司的素祭的(6:1-7:36)

- 7。摘要(7:37-38)

二。機構的神職人員(8:1-10:20)

- 亞倫答:出家和他的兒子(章8)

- B.亞倫使得第一犧牲(章9)

- C.判斷上拿答,亞比戶(章10)

三。不潔及其治療(11:1-16:24)

- A.不潔淨的動物(章11)

- B.不潔引起分娩(章12)

- C.不潔性疾病(章13)

- 疾病D.卸妝(章14)

- E.不潔放電(章15)

- F.純化不潔(章16)會幕

四。處方實用聖潔(的神聖代碼(chs. 17-26)

- A.犧牲和食品(章17)

- B.性的行為(章18)

- C.睦鄰(ch.19)

- D.嚴重罪行(章20)

- E.規則祭司(章21)

- F.規則吃的犧牲(章22)

- G.節日(ch.23)

- H.規則帳幕(章24:1-9)

- 一,褻瀆(章24:10-23)

- J.休假和禧年(章25)

- K.勸遵守法律:祝福與咒詛(章26)

五,還願的禮品換領(章27)

Summary[edit]

Chapters 1–5 describe the various sacrifices from the sacrificers' point of view, although the priests are essential for handling the blood. Chapters 6–7 go over much the same ground, but from the point of view of the priest, who, as the one actually carrying out the sacrifice and dividing the "portions", needs to know how this is to be done. Sacrifices are to be divided between God, the priest, and the one offerer, although in some cases the entire sacrifice is a single portion consigned to God—i.e., burnt to ashes.[8]

Chapters 7–10 describe the consecration (by Moses) of Aaron and his sons as the first priests, the first sacrifices, and God's destruction of two of Aaron's sons for ritual offenses. The purpose is to underline the character of altar priesthood (i.e., those priests empowered to offer sacrifices to God) as an Aaronite privilege, and the restrictions on their position.[9]

With sacrifice and priesthood established, chapters 11–15 instruct the lay people on purity (or cleanliness). Eating certain animals produces uncleanliness, as does giving birth; certain skin diseases (but not all) are unclean, as are certain conditions affecting walls and clothing (mildew and similar conditions); and genital discharges, including female menses and male gonorrhea, are unclean. The reasoning behind the food rules are obscure; for the rest the guiding principle seems to be that all these conditions involve a loss of "life force", usually but not always blood.[10]

Leviticus 16 concerns the Day of Atonement. This is the only day on which the High Priest is to enter the holiest part of the sanctuary, the holy of holies. He is to sacrifice a bull for the sins of the priests, and a goat for the sins of the laypeople. A third goat is to be sent into the desert to "Azazel", bearing the sins of the whole people. Azazel may be a wilderness-demon, but its identity is mysterious.[11]

Chapters 17–26 are the Holiness code. It begins with a prohibition on all slaughter of animals outside the Temple, even for food, and then prohibits a long list of sexual contacts and also child sacrifice. The "holiness" injunctions which give the code its name begin with the next section: penalties are imposed for the worship of Molech, consulting mediums and wizards, cursing one's parents and engaging in unlawful sex. Priests are instructed on mourning rituals and acceptable bodily defects. Blasphemy is to be punished with death, and rules for the eating of sacrifices are set out; the calendar is explained, and rules for sabbatical and Jubilee years set out; and rules are made for oil lamps and bread in the sanctuary; and rules are made for slavery.[12] The code ends by telling the Israelites they must choose between the law and prosperity on the one hand, or, on the other, horrible punishments, the worst of which will be expulsion from the land.[13]

Chapter 27 is a disparate and probably late addition telling about persons and things dedicated to the Lord and how vows can be redeemed instead of fulfilled.[14]

Line 74 edits arise from the following sources: [15]; [16]

摘要[ 編輯]

第1-5章描述從sacrificers的角度來看,各種犧牲,雖然祭司是處理血液是必不可少的。第6-7章去了大致相同的理由,但是從牧師,誰,作為一個實際執行的犧牲和除以“部分”,需要知道這是怎麼做的地步。犧牲是必須的神,牧師,和一個發貨人之間的分歧,但在某些情況 下,整個祭祀是交給老天爺,即燒成灰燼一個部分。[ 8 ]

第7-10章描述的奉獻(由摩西的)亞倫和他的兒子作為第一個祭司,第一犧牲,和兩個亞倫的兒子為祭祀罪行神的破壞。其目的是強調壇聖職的字符(即那些祭司有權向神獻祭)作為Aaronite特權,他們的位置的限制。[ 9 ]

用犧牲和祭司成立,章11-15指示外行人的純度(或清潔)。吃某些動物產生不潔一樣,生完孩子,某些皮膚病(但不是全部)是不潔的,因為是影響牆壁和衣服(黴菌和類似的條件下)一定的條件;和生殖器排放,包括月經的女性和男性淋病,是不潔。背後的食品規則的推理是模糊的;為休息的指導原則似乎是,所有這些條件涉及“生命的力量”損失,通常但並不總是血[ 10 ]

利未記16章是關於贖罪日。這是在其大祭司是進入聖所的最神聖的一部分,唯一的一天至聖所。他就是犧牲一隻公牛犢為祭司的罪孽,和一隻山羊為教友的罪。第三個山羊被發送到曠野,是“ 阿撒瀉勒 “,承載著全國人民的罪惡。阿撒瀉勒可能成為曠野妖,但其身份是神秘的。[ 11 ]

17-26章是聖潔的代碼。它一開始就禁止在寺廟外面的動物屠宰所有,即使是食物,然後禁止性接觸,也是孩子犧牲一個長長的清單。對“聖潔”禁令,從而使該代碼它的名字開始與下一節:處罰徵收的崇拜摩洛,諮詢介質和嚮導,咒罵自己的父母和從事非法的性行為。神父被指示的哀悼儀式和接受的身體缺陷。褻瀆,是與死神進行處罰,並為犧牲的飲食規則載,歷解釋,以及休假和規則禧年載;和規則的油燈和麵包的聖所作出的;及規則為使奴隸制。[ 12 ]中的代碼告訴以色列人,他 們必須一方面是法律和繁榮之間進行選擇,或者,另一方面,可怕的懲罰,其中最嚴重的將是被驅逐出土地結束。[ 13 ]

第27章是一個完全不同的,可能後期除了講述奉獻給主,並誓言如何可以兌換,而不是滿足的人與事。[ 14 ]

Composition[edit]

The majority of scholars agree that the Pentateuch received its final form during the Persian period (538–332 BCE).[17]Nevertheless, they also agree that Leviticus had a long period of growth, with many additions and editings, before reaching that form.[5]

The entire book of Leviticus is composed of Priestly literature.[18] Most scholars see chapters 1–16 (the Priestly code) and chapters 17–26 (the Holiness code) as the work of two related schools, but while the Holiness material employs the same technical terms as the Priestly code, it broadens their meaning from pure ritual to the theological and moral, turning the ritual of the Priestly code into a model for the relationship of Israel to God: as the tabernacle is made holy by the presence of the Lord and kept apart from uncleanliness, so He will dwell among Israel when Israel is purified (made holy) and separated from other peoples.[19]

The ritual instructions in the Priestly code apparently grew from priests giving instruction and answering questions about ritual matters; the Holiness code (or H) used to be regarded as a separate document later incorporated into Leviticus, but it seems better to think of the Holiness authors as editors who worked with the Priestly code and actually produced Leviticus as we now have it.[20]

組成[ 編輯]

多數學者一致認為,摩西五經中的波斯 時期(公元前538-332)接受了它的最終形態。[ 17 ]不過,他們也同意利未記增長了很長一段時間,有許多補充和編輯位點,達到該表單之前, ,[ 5 ]

利未記整本書是由祭司文學。[ 18 ]多數學者認為章1-16(在祭司碼)和章節17-26(在聖潔的代碼),作為兩個相關學校的工作,但同時聖潔材料採用相同的技術術語為祭司的代碼,它拓寬了自己的意思從單純的儀式,神學和道德,轉彎祭司代碼到模型為以色列神的關係的儀式:為帳幕是由聖所的存在主並保持遠離不潔,所以他要與以色列住在以色列純化(成為聖潔)和其他民族分離。[ 19 ]

在祭司碼的儀式顯然說明從增長祭司給予指導和回答有關禮儀事項的問題;聖潔的代碼(或H)曾經被視為一個單獨的文件後併入利,但似乎不如想像的聖潔作者因為誰曾與祭司代碼和實際編輯製作利未記,因為我們現在擁有它。[ 20 ]

Themes[edit]

Ritual[edit]

The rituals of Leviticus have a theological meaning concerning Israel's personal relationship with its God.[21] Ritual, therefore, is not a series of actions undertaken for their own sake, but a means of maintaining the relationship between God, the world, and humankind.[22]

Sacrifice[edit]

The Priestly theology of sacrifice begins with the Creation, when humankind is not given permission to eat meat (Genesis 1:26–30); after the Flood God gives permission to men to slaughter animals and eat their meat, but the animals are to be offered as sacrifices (Genesis 9:3–4).[23] Sacrifice is in a sense a gift (offering) to God, but also involves the transfer of the offering from the everyday to the sacred; those who eat meat are eating a sanctified meal,[24] and God's share in this is the "pleasing odour" released as the offering (incense or meat) is burnt.[25]

In Leviticus, sacrifice is to be offered only by priests. This does not conform with the picture given elsewhere in the bible, where sacrifices are offered by a wide range of people (e.g. Manoah the judge, Samuel and Elijah the prophets, and kings Saul, David and Solomon, none of whom are priests) and the general impression is that any head of family could make a sacrifice. Most of these sacrifices are burnt offerings, and there is no mention of sin offerings. For these reasons there is a widespread scholarly view that the sacrificial rules of Leviticus 1–16 were introduced after the Babylonian exile, when circumstances allowed the priestly writers to describe the rituals so as to express their worldview of an idealised Israel living its life as a holy community in observance of the priestly prescriptions.[26]

主題[ 編輯]

儀式[ 編輯]

利未記的儀式有關於與以色列神的個人關係的神學意義。[ 21 ]儀式,因此,是不是一系列承諾為自己著想的行動,但保持上帝,世界和人類之間的關係的一種手段。[ 22 ]

犧牲[ 編輯]

獻祭的祭司神學始於創造,人類的時候不給吃肉(創世記1:26-30)許可;洪水上帝給的許可後,男人屠宰的動物,吃它們的肉,但動物是。提供作為獻祭(創9:3-4)[ 23 ]犧牲是在某種意義上的禮物(提供)給上帝,但也涉及發售從日常轉移到神聖的,那些誰吃的肉是吃聖潔餐,[ 24 ]和神在這個份額是“令人愉快的氣味”發布的募股(香或肉)被燒毀。[ 25 ]

在利未記,犧牲是只由神父提供。這不符合聖經,其中的犧牲是由各種各樣的人(如瑪挪亞的法官,薩穆埃爾和以利亞先知,君王掃羅,大衛和所羅門,沒有一個人是祭司)提供給其他地方的圖片和一致一般的印象是,任何家庭的頭可以做出犧牲。大多數這些犧牲是燔祭,也沒有提及贖罪祭的。出於這些原因,有一種普遍的學術觀點,即利未記1-16的祭祀規則後推出巴比倫流亡,在情況允許的祭司作家描述的儀式,以表達一種理想化他們對以色列的世界觀生活的生活,作為一個聖社區慶祝司鐸處方。[ 26 ]

Priesthood[edit]

The main function of the priests is service at the altar, and only the sons of Aaron are priests in the full sense.[27] (Ezekiel also distinguishes between altar-priests and lower Levites, but in Ezekiel the altar-priests are called sons of Zadok instead of sons of Aaron; many scholars see this as a remnant of struggles between different priestly factions in First Temple times, resolved by the Second Temple into a hierarchy of Aaronite altar-priests and lower-level Levites, including singers, gatekeepers and the like).[28]

In chapter 10, God kills Nadab and Abihu, the oldest sons of Aaron, for offering "strange incense". Fortunately, Aaron has two sons left. Commentators have read various messages in the incident: a reflection of struggles between priestly factions in the post–Exilic period (Gerstenberger); or a warning against offering incense outside the Temple, where there might be the risk of invoking strange gods (Milgrom). In any case, the sanctuary has been polluted by the bodies of the two dead priests, leading into the next theme, holiness.[29]

聖職[ 編輯]

祭司的主要功能是在祭壇的服務,只有兒子亞倫的祭司在完全意義上的。[ 27 ](以西結書也壇的祭司和利未人低區分,但在以西結書壇祭司被稱為兒子撒督代替亞倫的兒子,許多學者認為這是在第一聖殿時期的不同祭司派別之間的鬥爭,通過二王廟分解成Aaronite壇的祭司和較低級別的利未人,包括歌手,守門的層次結構的殘餘和等)等。[ 28 ]

在第10章,神殺拿答,亞比戶,亞倫的大兒子,為提供“怪香”。幸運的是,亞倫有兩個兒子離開了。有論者在事件中讀取各種消息:在被擄後時期(Gerstenberger)祭司的派別之間鬥爭的反映,或對提供的寺廟,那裡可能是調用外邦神(米爾格羅姆)的風險外香警告。在任何情況下,保護區已被污染的兩個死牧師的屍體,領先進入下一個主題,聖潔。[ 29 ]

不潔和純度[ 編輯]

儀式的純潔性是必不可少的以色列人要能接近神,並保持社會的一部分。[ 9 ]不潔威脅聖潔; [ 30 ]章11-15審查不潔的各種原因,並說明其將恢復潔淨的儀式; [ 31 ]清潔是通過觀察對性行為,家庭關係,土地所有權,拜,祭,並遵守聖日的規則來維持。[ 32 ]

耶和華常與以色列在至聖所。所有的祭司儀式的重點是耶和華,建設和維護一個神聖的空間,而是罪惡產生的雜質,如做如分娩的日常活動;雜質污染了聖潔的居所。若不淨化儀式的神聖空間,可能會導致神離開的時候,這將是災難性的。[ 33 ]

Uncleanliness and purity[edit]

Ritual purity is essential for an Israelite to be able to approach God and remain part of the community.[9] Uncleanliness threatens holiness;[30] Chapters 11–15 review the various causes of uncleanliness and describe the rituals which will restore cleanliness;[31] cleanliness is to be maintained through observation of the rules on sexual behaviour, family relations, land ownership, worship, sacrifice, and observance of holy days.[32]

Yahweh dwells with Israel in the holy of holies. All of the priestly ritual is focused on Yahweh and the construction and maintenance of a holy space, but sin generates impurity, as do everyday events such as childbirth; impurity pollutes the holy dwelling place. Failure to ritually purify the sacred space could result in God leaving, which would be disastrous.[33]

Atonement[edit]

Through sacrifice the priest "makes atonement" for sin and the offerer is forgiven (but only if God accepts the sacrifice—forgiveness comes only from God).[34] Atonement rituals involve blood, poured or sprinkled, as the symbol of the life of the victim: the blood has the power to wipe out or absorb the sin.[35] The role of atonement is reflected structurally in two-part division of the book: chapters 1–16 call for the establishment of the institution for atonement, and chapters 17–27 call for the life of the atoned community in holiness.[36]

贖罪[ 編輯]

通過犧牲的神父“,使贖罪”罪和發貨人是情有可原的(但只有只有神接受的犧牲,寬恕是從神而來)。[ 34 ]贖罪的儀式包括血,或倒灑,作為生命的象徵受害人:血液有消滅或吸收罪惡的力量。[ 35 ]贖罪的作用在結構上體現在本書的兩部分分工:章1-16呼籲建立該機構的贖罪,和章節17-27呼籲贖社會在聖潔的生活。[ 36 ]

聖潔[ 編輯]

“你們要聖潔,因為我耶和華你們的神是聖潔的”章17-26的一貫主題是重複的短語,[ 32 ]聖潔的古代以色列有不同的含義在當代的用法:它可能被視為“神性”的神,一種無形但實際和潛在的危險力量。[ 37 ]具體的對象,甚至幾天的時間,可以是聖潔的,但他們得到聖潔的神,第七天,帳幕,和被連接的所有的祭司從神得到他們的聖潔。[ 38 ]因此,以色列不得不維護自己的聖潔,以神一起安全地生活。[ 39 ]

需要對聖潔被定向到應許之地(藏迦南),這裡的猶太人將成為一個聖潔的人:“你不該做,因為他們在埃及,你居住的土地,你就不會做,因為他們做在迦南的,我給你們帶來的土地......你應當做我的典章,守我的律例...我是耶和華你的神“(章18:3)。[ 40 ]

Holiness[edit]

The consistent theme of chapters 17–26 is the repeated phrase, "Be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy."[32] Holiness in ancient Israel had a different meaning than in contemporary usage: it might have been regarded as the "god-ness" of God, an invisible but physical and potentially dangerous force.[37] Specific objects, or even days, can be holy, but they derive holiness from being connected with God—the seventh day, the tabernacle, and the priests all derive their holiness from God.[38] As a result, Israel had to maintain its own holiness in order to live safely alongside God.[39]

The need for holiness is directed to the possession of the Promised Land (Canaan), where the Jews will become a holy people: "You shall not do as they do in the land of Egypt where you dwelt, and you shall not do as they do in the land of Canaan to which I am bringing you...You shall do my ordinances and keep my statutes...I am the Lord, your God" (ch. 18:3).[40]

隨後的傳統[ 編輯]

利未記構成的主要來源猶太律法,並且有證據表明,這是第一本書塔納赫教教育的拉比系統在塔木德時間。一個可能的原因可能是所有的書籍,聖經,利未記是最接近是純粹致力於mitzvot及其研究從而能夠去手牽手與他們的表現。有兩種主要的米大示於利-的halakhic 1(Sifra)和一個更aggadic 1(Vayikra拉巴)。

新約聖經的著作,如希伯來書講的基督的血,使用的語言贖罪祭的利未記。[ 35 ]戈登·溫漢姆在他的評論在利未記表示的設想是基督教中刪除這些需要犧牲動物話:“隨著基督的死是唯一足夠的”燔祭“。被提供了一勞永逸的,因此動物獻祭這預示基督的犧牲進行了過時的” [ 41 ]

基督徒一般有觀點認為新約 取代(即替換)在摩西的律法,其中利未記是一個核心部分。基督徒因此,與許多猶太人,不遵守有關行為的整個範圍利未記“禁令,從吃貝類在自己的衣服”條紋“的穿著禁令。然而,在基督教和猶太教,利未記18:22和20:13歷來被解釋為反對同性戀行為明確毯禁令。[ 42 ]

Subsequent tradition[edit]

Leviticus constitutes a major source of Jewish law, and there is evidence that it was the first book of the Tanakh taught in the Rabbinic system of education in Talmudic times. A possible reason may be that, of all the books of the Torah, Leviticus is the closest to being purely devoted to mitzvot and its study thus is able to go hand-in-hand with their performance. There are two mainMidrashim on Leviticus—the halakhic one (Sifra) and a more aggadic one (Vayikra Rabbah).

New Testament writings such as the letter to the Hebrews speak of the blood of Christ, using the language of the sin offering in Leviticus.[35] Gordon Wenham in his commentary on Leviticus expresses the idea that Christianity removed the need for animal sacrifice in these words: "With the death of Christ the only sufficient "burnt offering" was offered once and for all, and therefore the animal sacrifices which foreshadowed Christ's sacrifice were made obsolete."[41]

Christians generally have the view that the New Covenant supersedes (i.e., replaces) the Law of Moses, of which Leviticus is a central part. Christians therefore, unlike many Jews, do not observe Leviticus' prohibitions on a whole range of behaviors, from the ban on eating shellfish to the wearing of "fringes" on their garments. However, in both Christianity and Judaism, Leviticus 18:22 and 20:13 have historically been interpreted as clear blanket prohibitions against homosexual acts.[42]

根據猶太教每週Torah部分內容[ 編輯]

- 有關詳細內容,請參見:

- Vayikra,在利未記1-5的犧牲法律

- Tzav,在利未記6-8:祭祀,協調的祭司

- Shemini,在利未記9-11:幕奉獻,外星人火,飲食規律

- Tazria,在利未記12-13:生育,皮膚病,服裝

- Metzora,在利未記14-15:皮膚疾病,受感染的房子,生殖器放電

- Acharei MOT,在利未記16-18:贖罪日,集中式的產品,性行為

- Kedoshim,在利未記19-20:聖潔,懲罰越軌

- EMOR,在利未記21-24:規則祭司,是聖潔的日子裡,燈光和麵包,褻瀆

- 貝哈爾,在利未記25-25:休假一年,債務奴役的限制

- Bechukotai,在利未記26-27:祝福和詛咒,付款誓言

Contents according to Judaism's weekly Torah portions[edit]

- For detailed contents see:

- Vayikra, on Leviticus 1–5: Laws of the sacrifices

- Tzav, on Leviticus 6–8: Sacrifices, ordination of the priests

- Shemini, on Leviticus 9–11: Tabernacle consecrated, alien fire, dietary laws

- Tazria, on Leviticus 12–13: Childbirth, skin disease, clothing

- Metzora, on Leviticus 14–15: Skin disease, infected houses, genital discharges

- Acharei Mot, on Leviticus 16–18: Yom Kippur, centralized offerings, sexual practices

- Kedoshim, on Leviticus 19–20: Holiness, penalties for transgressions

- Emor, on Leviticus 21–24: Rules for priests, holy days, lights and bread, a blasphemer

- Behar, on Leviticus 25–25: Sabbatical year, debt servitude limited

- Bechukotai, on Leviticus 26–27: Blessings and curses, payment of vows

References[edit]

- ^ Wenham, p.3

- ^ Gorman, pp.4–5, 14–16

- ^ Wenham, p.8 ff.

- ^ Gerstenberger, p.4

- ^ a b Grabbe (1998), p.92

- ^ Wenham, pp.3–4

- ^ Gorman, pp.2–3

- ^ Grabbe (2006), p.208

- ^ a b Kugler, Hartin, p.82

- ^ Kugler, Hartin, pp.82–83

- ^ Kugler, Hartin, p.83

- ^ http://niv.scripturetext.com/leviticus/25.htm

- ^ Kugler, Hartin, pp.83–84

- ^ Kugler, Hartin, p.84

- ^ Calvin's Commentaries, Volume II, "Harmony of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, p177ff

- ^ Bonar, Andrew, Leviticus, p.75ff.

- ^ Newsom, p.26

- ^ Levine, p.11

- ^ Houston, p.102

- ^ Houston, pp.102–103

- ^ Davies, Rogerson, p.157

- ^ Balentine (1999) p.150

- ^ Rogerson, p.19

- ^ Davies, Rogerson, pp.103–106

- ^ Davies, Rogerson, p.153

- ^ Davies, Rogerson, pp.152, 155

- ^ Grabbe (2006), p.211

- ^ Grabbe (2006), p.211 (fn.11)

- ^ Houston, p.110

- ^ Davies, Rogerson, p.101

- ^ Marx, p.104

- ^ a b Balentine (2002), p.8

- ^ Gorman, pp.10–11

- ^ Houston, p.106

- ^ a b Houston, p.107

- ^ Knierim, p.114

- ^ Rodd, p.7

- ^ Brueggemann, p.99

- ^ Rodd, p.8

- ^ Clines, p.56

- ^ Wenham, p.65

- ^ Jeffrey S. Siker, Homosexuality and Religion(Greenwood Publishing Group 2007 ISBN 978-0-31333088-9), p. 66–67

Bibliography[edit]

Translations of Leviticus[edit]

- Leviticus at Bible gateway

Commentaries on Leviticus[edit]

- Balentine, Samuel E (2002). Leviticus. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664237356.

- Gerstenberger, Erhard S (1996). Leviticus: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664226732.

- Gorman, Frank H (1997). Divine presence and community: a commentary on the Book of Leviticus. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802801104.

- Grabbe, Lester (1998). "Leviticus". In John Barton. Oxford Bible Commentary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198755005.

- Houston, Walter J (2003). "Leviticus". In James D. G. Dunn, John William Rogerson. Eerdmans Bible Commentary. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802837110.

- Kleinig, John W (2004). Leviticus. Concordia Publishing House. ISBN 9780570063179.

- Wenham, Gordon (1979). The book of Leviticus. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802825223.

General[edit]

- Balentine, Samuel E (1999). The Torah's vision of worship. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451418088.

- Bandstra, Barry L (2004). Reading the Old Testament: an introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 9780495391050.

- Brueggemann, Walter (2002). Reverberations of faith: a theological handbook of Old Testament themes. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 9780664222314.

- Campbell, Antony F; O'Brien, Mark A (1993). Sources of the Pentateuch: texts, introductions, annotations. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451413670.

- Clines, David A (1997). The theme of the Pentateuch. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9780567431967.

- Davies, Philip R; Rogerson, John W (2005). The Old Testament world. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780664230258.

- Dawes, Gregory W (2005). Introduction to the Bible. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814628355.

- Gilbert, Christopher (2009). A Complete Introduction to the Bible. Paulist Press. ISBN 9780809145522.

- Grabbe, Lester (2006). "The priests in Leviticus". In Rolf Rendtorff, Robert A. Kugler. The Book of Leviticus: Composition and Reception. Brill. ISBN 9789004126343.

- Knierim, Rolf P (1995). The task of Old Testament theology: substance, method, and cases. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802807151.

- Kugler, Robert; Hartin, Patrick (2009). An Introduction to the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802846365.

- Levine, Baruch (2006). "Leviticus: Its Literary History and Location in Biblical Literature". In Rolf Rendtorff, Robert A. Kugler. The Book of Leviticus: Composition and Reception. Brill. ISBN 9789004126343.

- Marx, Alfred (2006). "The theology of the sacrifice according to Leviticus 1–7". In Rolf Rendtorff, Robert A. Kugler. The Book of Leviticus: Composition and Reception. Brill.ISBN 9789004126343.

- McDermott, John J (2002). Reading the Pentateuch: a historical introduction. Pauline Press. ISBN 9780809140824.

- Newsom, Carol Ann (2004). The self as symbolic space: constructing identity and community at Qumran. BRILL. ISBN 9789004138032.

- Rodd, Cyril S (2001). Glimpses of a strange land: studies in Old Testament ethics. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567087539.

- Rogerson, J.W (1991). Genesis 1–11. T&T Clark. ISBN 9780567083388.

- Van Seters, John (1998). "The Pentateuch". In Steven L. McKenzie, Matt Patrick Graham. The Hebrew Bible today: an introduction to critical issues. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9780664256524.

- Ska, Jean-Louis (2006). Introduction to reading the Pentateuch. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 9781575061221.

- Wenham, Gordon (2003). Exploring the Old Testament: The Pentateuch. SPCK.

External links[edit]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Online versions of Leviticus:

- Hebrew:

- Leviticus at Mechon-Mamre (Jewish Publication Society translation)

- Leviticus (The Living Torah) Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan's translation and commentary at Ort.org

- Vayikra—Levitichius (Judaica Press) translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- ויקרא Vayikra—Leviticus (Hebrew—English at Mechon-Mamre.org)

- Christian translations:

Related article:

- Book of Leviticus article (Jewish Encyclopedia)

- The Literary Structure of Leviticus (chaver.com)

Free Online Bibliography on Leviticus:

|

Book of Leviticus

|

||

| Preceded by Exodus |

Hebrew Bible | Succeeded by Numbers |

| Christian Old Testament |

||

|

||

參考文獻[ 編輯]

- ^ 威納姆,第3頁

- ^ 戈爾曼,PP.4-5,14-16

- ^ 威納姆,第8頁頁。

- ^ Gerstenberger,第4頁

- ^ 一個 b Grabbe(1998),第92頁

- ^ 威納姆,PP.3-4

- ^ 戈爾曼,PP.2-3

- ^ Grabbe(2006年),第208頁

- ^ 一個 b 庫格勒,哈廷,第82頁

- ^ 庫格勒,哈廷,pp.82-83

- ^ 庫格勒,哈廷,第83頁

- ^ http://niv.scripturetext.com/leviticus/25.htm

- ^ 庫格勒,哈廷,pp.83-84

- ^ 庫格勒,哈廷,第84頁

- ^ 加爾文的評論,第二卷,“和諧出埃及記,利未記,民數記,申命記,p177ff

- ^ 博納,安德魯,利未記,p.75ff。

- ^ 紐森,第26頁

- ^ 萊文,第11頁

- ^ 休斯敦,第102頁

- ^ 休斯敦,pp.102-103

- ^ 戴維斯,羅傑森,第157頁

- ^ 巴倫坦(1999)第150頁

- ^ 羅傑森,第19頁

- ^ 戴維斯,羅傑森,,103-106

- ^ 戴維斯,羅傑森,第153頁

- ^ 戴維斯,羅傑森,pp.152,155

- ^ Grabbe(2006年),第211頁

- ^ Grabbe(2006年),第211頁(fn.11)

- ^ 休斯敦,第110頁

- ^ 戴維斯,羅傑森,第101頁

- ^ 馬克思,第104頁

- ^ 一個 b 巴倫坦(2002年),第8頁

- ^ 戈爾曼,:10-11

- ^ 休斯敦,第106頁

- ^ 一個 b 休斯敦,第107頁

- ^ 尼里姆,第114頁

- ^ 羅德,第7頁

- ^ 布呂格曼,第99頁

- ^ 羅德,第8頁

- ^ 漸變群,第56頁

- ^ 威納姆,第65頁

- ^ 的Jeffrey S. Siker,同性戀和宗教(格林伍德出版集團2007 ISBN 978-0-31333088-9),第 66-67

參考文獻[ 編輯]

利未記的翻譯[ 編輯]

- 利未記在聖經網關

在利未記評[ 編輯]

- 巴倫坦,塞繆爾·E(2002)。利未記。威斯敏斯特約翰·諾克斯出版社ISBN 9780664237356。

- 。Gerstenberger,艾哈德(1996)利未記:評注。威斯敏斯特約翰·諾克斯出版社ISBN 9780664226732。

- 。戈爾曼,弗蘭克·H(1997)神的存在和社區:利未記書的一篇評論。Eerdmans。ISBN 9780802801104。

- Grabbe,萊斯特(1998)。 “ 利”。在約翰·巴頓。牛津聖經註釋。牛津大學出版社,ISBN 9780198755005。

- 休斯頓,沃爾特Ĵ(2003)。 “ 利未記”。在詹姆斯DG鄧恩,約翰·威廉·羅傑森。Eerdmans聖經註釋。Eerdmans。ISBN 9780802837110。

- Kleinig,約翰·W(2004年)。利未記。協和出版社ISBN 9780570063179。

- 威翰,戈登(1979)。利未記。Eerdmans。ISBN 9780802825223。

一般[ 編輯]

- 巴倫坦,塞繆爾·E(1999)。崇拜的托拉的願景。豐澤出版社ISBN 9781451418088。

- Bandstra,巴里L(2004)。讀舊約:介紹了希伯來文聖經。沃茲沃思。ISBN 9780495391050。

- 。布呂格曼,瓦爾特(2002)信念迴響:舊約主題的神學手冊。威斯敏斯特約翰·諾克斯。ISBN 9780664222314。

- 坎貝爾,安東尼F;奧布萊恩,馬克(1993),摩西五經的來源:文本,介紹,註釋。豐澤出版社ISBN 9781451413670。

- 世界範圍內的減少,大衛·A(1997),摩西五經的主題。謝菲爾德學術出版社,ISBN 9780567431967。

- 戴維斯,菲利普R;羅傑森,約翰·W(2005年)。舊約世界。禮儀出版社,ISBN 9780664230258。

- 道斯,格雷戈里W(2005年)。聖經導論。禮儀出版社,ISBN 9780814628355。

- 吉爾伯特,克里斯托弗(2009)。一個完整的聖經導論。Paulist新聞,國際標準書號 9780809145522。

- Grabbe,萊斯特(2006), “ 利未記祭司”。在羅爾夫Rendtorff,羅伯特·A·庫格勒。利未記:組成和接待。布里爾。ISBN 9789004126343。

- 尼里姆,羅爾夫·P(1995)。舊約神學的任務:物質,方法和案例。Eerdmans。ISBN 9780802807151。

- 庫格勒,羅伯特;哈廷,帕特里克(2009)介紹聖經。Eerdmans。ISBN 9780802846365。

- 萊文,巴魯克(2006)。 “ 利未記:它的文學史和地點在聖經文學”。在羅爾夫Rendtorff,羅伯特·A·庫格勒。利未記:組成和接待。布里爾。ISBN 9789004126343。

- 馬克思,阿爾弗雷德(2006) “ 的犧牲根據利未記1-7的神學”。在羅爾夫Rendtorff,羅伯特·A·庫格勒。利未記:組成和接待。布里爾。ISBN 9789004126343。

- 麥克德莫特,約翰Ĵ(2002)。讀五經:一個歷史的介紹。寶蓮出版社ISBN 9780809140824。

- 紐森,卡羅爾·安(2004)。自我為象徵性的空間:構建虛擬形象和社區在庫姆蘭。很棒。ISBN 9789004138032。

- 。羅德,西里爾S(2001)一個陌生國度一瞥:在舊約倫理的研究。電訊克拉克。ISBN 9780567087539。

- 羅傑森,JW(1991),創世紀1-11。電訊克拉克。ISBN 9780567083388。

- 凡Seters,約翰(1998)。 “ 摩西五經”。在史蒂芬斯,馬特·帕特里克·格雷厄姆。希伯來聖經今日:介紹關鍵問題。威斯敏斯特約翰·諾克斯出版社ISBN 9780664256524。

- 斯卡,讓-路易(2006),介紹讀五經。Eisenbrauns。ISBN 9781575061221。

- 。威翰,戈登(2003)探討舊約:摩西五經。SPCK。

外部鏈接[ 編輯]

| 維基文庫有與此相關的文章原文: |

在線版本利未記:

- 希伯來語:

- 利未記在Mechon -幔利(猶太出版協會翻譯)

- 利未記(活的聖經)拉比ARYEH卡普蘭的翻譯和評論在Ort.org

- Vayikra-Levitichius(猶太文物出版社)翻譯[與拉什的解說]在Chabad.org

- ויקרא Vayikra -利未記(希伯來語,英語在Mechon-Mamre.org)

相關文章:

免費在線參考書目利未記:

|

利未記書

|

||

| 在之前出埃及記 | 希伯來聖經 | 通過成功數 |

| 基督教 舊約 |

||

留言列表

留言列表

{{ article.title }}

{{ article.title }}