Acts使徒行傳

Acts of the Apostles

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Matthew · Mark · Luke · John |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

| Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

The Acts of the Apostles (Ancient Greek: Πράξεις τῶν Ἀποστόλων, Práxeis tôn Apostólōn; Latin: Āctūs Apostolōrum), often referred to simply as Acts, is the fifth book of the New Testament; Acts outlines the history of the Apostolic Age.

Acts tells the story of the Early Christian church, with particular emphasis on the ministry of the apostles Simon Peterand Paul of Tarsus, who are the central figures of the middle and later chapters of the book. The early chapters, set inJerusalem, discuss Jesus' Resurrection, his Ascension, the Day of Pentecost, and the start of the apostles' ministry. The later chapters discuss Paul's conversion, his ministry, and finally his arrest, imprisonment, and trip to Rome. A major theme of the book is the expansion of the Holy Spirit's work from the Jews, centering in Jerusalem, to the Gentilesthroughout the Roman Empire.

It is almost universally agreed that the author of Acts also wrote the Gospel of Luke, but modern scholarship has rejected the tradition that the author of Luke-Acts was Luke the companion of Paul, a contemporary of the events the book describes and an eyewitness to many of them.[1]

Composition and setting[edit]

[edit]

The title "Acts of the Apostles" (Greek Πράξεις ἀποστόλων Praxeis Apostolon) was first used by Irenaeus in the late 2nd century. It is not known whether this was an existing title or one invented by Irenaeus; it does seem clear, however, that it was not given by the author.[2]

The gospel of Luke and Acts make up a two-volume work which scholars call Luke-Acts.[3] Together they account for 27.5% of the New Testament, the largest contribution by a single author, providing the framework for both the Church's liturgical calendar and the historical outline into which later generations have fitted their idea of the story of Jesus and the early church.[4]

The author is not named in either volume.[5] According to a Church tradition dating from the 2nd century, he was the "Luke" named as a companion of the apostle Paul in three of the letters attributed to Paul himself; this view is still sometimes advanced, but "a critical consensus emphasizes the countless contradictions between the account in Acts and the authentic Pauline letters."[6] (An example can be seen by comparing Acts' accounts of Paul's conversion (Acts 9:1-31, 22:6-21, and 26:9-23) with Paul's own statement that he remained unknown to Christians in Judea after that event (Galatians 1:17-24).)[7] He admired Paul, but his theology was significantly different from Paul's on key points and he does not (in Acts) represent Paul's views accurately.[8] He was educated, a man of means, probably urban, and someone who respected manual work, although not a worker himself; this is significant, because more high-brow writers of the time looked down on the artisans and small business-people who made up the early church of Paul and were presumably Luke's audience.[9]

Most experts date the composition of Luke-Acts to around 80-90 CE, although some suggest 90-110.[10] The eclipse of the traditional attribution to Luke the companion of Paul has meant that an early date for the gospel is now rarely put forward.[6] There is evidence, both textual (the conflicts between Western and Alexandrian manuscript families) and from the Marcionite controversy (Marcion was a 2nd century heretic who produced his own version of Christian scripture based on Luke's gospel and Paul's epistles) that Luke-Acts was still being substantially revised well into the 2nd century.[11]

Genre and sources[edit]

The author of Luke-Acts adapted the eclectic genre of general history into a novel literary work lacking exact Classical analogies.[12] He describes his book as a "narrative" (diegesis), rather than as a gospel, and implicitly criticises his predecessors for not giving their readers the speeches of Jesus and the Apostles, the mark or a "full" report, and the means through which ancient historians conveyed the meaning of their narratives.[13]

Luke, as the author can be called for convenience, seems to have taken as his model the works of two respected Classical authors, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, who wrote a history of Rome, and the Jewish historian Josephus, author of a history of the Jews.[13] All three anchor the histories of their respective peoples by dating the births of the founders (Romulus, Moses and Jesus) and narrate the stories of the founders' births from God, so that they are sons of God.[13] Each founder taught authoritatively, appeared to witnesses after death, and ascended to heaven.[13] Crucial aspects of the teaching of all three concerned the relationship between rich and poor and the question of whether "foreigners" were to be received into the people.[13]

For his gospel Luke took as his sources the gospel of Mark, the sayings collection called the Q source, and a collection of unique material called the L (for Luke) source ("unique" meaning found only in Luke).[14] The sources for Acts are less certain. Mark was still used to some extent, by transposing incidents that Mark has in the life of Jesus to the time of the Apostles – for example, the material about "clean" and "unclean" in Mark 7 is used in Acts 10, and Mark's account of the accusation that Jesus has attacked the Temple (Mark 14:58) is used in Acts in a story about Stephen (Acts 6:14).[15] By and large, however, the sources for Acts can only be guessed at based on the internal evidence: the three "we" passages, for example, might point to such a source, and the traditional explanation is that they represent eye-witness accounts.[16] Further possible sources might include various other travel accounts, the stories in chapters 1-5 of the early years of the Jerusalem church (possibly two such sources, "Jerusalem A" and "Jerusalem B", as some narratives appear twice), the story of the conversion of Saul, and the story of the "Acts of Peter" - this list is not exhaustive, and not certain.[17]

[edit]

Luke was written to be read aloud to a group of Jesus-followers gathered in a house to share the Lord's supper.[13] The author assumes an educated Greek-speaking audience, but directs his attention to specifically Christian concerns rather than to the Greco-Roman world at large.[18] He begins his gospel with a preface addressed to "Theophilus", informing him of his intention to provide an "ordered account" of events which will lead his reader to "certainty.[9] He did not write in order to provide Theophilus with historical justification – "did it happen?" – but to encourage faith – "what happened, and what does it all mean?"[19]

Acts (or Luke-Acts) is a intended as a work of "edification."[20] Edification means "the empirical demonstration that virtue is superior to vice,"[21] but is not all of Luke's purpose. He also engages with the question of a Christian's proper relationship with the Roman Empire, the civil power of the day: could a Christian obey God and also Caesar? The answer is ambiguous.[22] The Romans never move against Jesus or his followers unless provoked by the Jews, in the trial scenes the Christian missionaries are always cleared of charges of violating Roman laws, and Acts ends with Paul in Rome proclaiming the Christian message under Roman protection; at the same time, Luke makes clear that the Romans, like all earthly rulers, receive their authority from Satan, while Christ is ruler of the kingdom of God. [23]

Luke-Acts can be also seen as a defense of (or "apology" for) the Jesus movement addressed to the Jews: the bulk of the speeches and sermons in Acts are addressed to Jewish audiences, with the Romans featuring as external arbiters on disputes concerning Jewish customs and law.[22] On the one hand Luke portrays the Christians as a sect of the Jews, and therefore entitled to legal protection as a recognised religion; on the other, Luke seems unclear as to the future God intends for Jews and Christians, celebrating the Jewishness of Jesus and his immediate followers while also stressing how the Jews had rejected God's promised Messiah.[24]

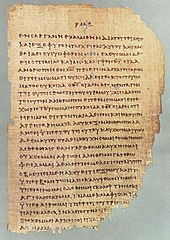

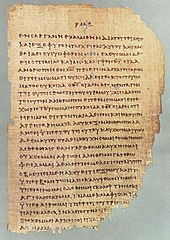

Manuscripts[edit]

The earliest manuscript witnesses (the technical term for written sources) for Luke's gospel are five 3rd-century papyrus fragments; the earliest complete attestations are 4th and 5th century.[25] These fall into two "families", the Western and the Alexandrian: the differences between these pose major difficulties, and the problem of the "original" text remains unresolved.[26] The dominant view is that the Western text represents a deliberate revision or editing, as the variations seem to form specific patterns.[27][Notes 1]

Like most biblical books, there are differences between the earliest surviving manuscripts of Acts. This is because there are three different families of Biblical texts, Byzantine, Western, and Alexandrian. The manuscripts from the Western text-type (as represented by the Codex Bezae) and the Alexandrian text-type (as represented by the Codex Sinaiticus) are the earliest survivors. The version of Acts preserved in the Western manuscripts contains about 10% more content than the Alexandrian version of Acts. Some scholars have struggled to determine if either of these two versions is closer to the original text composed by the original author. Within the Byzantine text family, a clear genuine reading emerges throughout the New Testament by comparing different manuscripts.

An early theory, suggested by Swiss theologian Jean LeClerc in the 17th century, posits that the longer Western version was a first draft, while the Alexandrian version represents a more polished revision by the same author. Adherents of this theory argue that even when the two versions diverge, they both have similarities in vocabulary and writing style—suggesting that the two shared a common author. However, it has been argued that if both texts were written by the same individual, they should have exactly identical theologies and they should agree on historical questions. Since some modern scholars do detect subtle theological and historical differences between the texts, such scholars do not subscribe to the rough-draft/polished-draft theory.

A second theory deals with the Byzantine text-type. This family includes extant manuscripts dating from the 5th century or later; however, papyrus fragments may be used to show that this text-type dates as early as the Alexandrian or Western text-types.[28] Many believe this group of texts comes from the original Book of Acts by looking at the Byzantine text for the whole of the New Testament. They argue that the oldest copies of this text family are likely to have been lost or destroyed over time with use, and therefore extant manuscripts cannot accurately date a text family. The great majority of Biblical manuscripts support the Byzantine family, from which a single reading for the New Testament is established. The Byzantine text-type was used for the 16th century Textus Receptus, the first Greek-language version of the New Testament to be printed by the printing press. The Textus Receptus, in turn, was used for the New Testament found in the English-language King James Bible. Today, the Byzantine text-type is the subject of renewed interest as the original form of the text from which the Western and Alexandrian text-types were derived.[29]

A third theory assumes common authorship of the Western and Alexandrian texts, but claims the Alexandrian text is the short first draft, and the Western text is a longer polished draft.

A fourth theory is that the longer Western text came first, but that later, some other redact or abbreviated some of the material, resulting in the shorter Alexandrian text.

In modern times, there is another theory that some have come to endorse. According to this new theory, the shorter Alexandrian text is closer to the original, and the longer Western text is the result of later insertion of additional material into the text.[30] In 1893, Sir W. M. Ramsay in The Church in the Roman Empire held that theCodex Bezae (the Western text) rested on a recension made in Asia Minor (somewhere between Ephesus and southern Galatia), not later than about the middle of the 2nd century. Some believe the revision in question was the work of a single reviser, who in his changes and additions expressed the local interpretation put upon Acts in his own time. His aim, in suiting the text to the views of his day, was partly to make it more intelligible to the public, and partly to make it more complete. To this end he "added some touches where surviving tradition seemed to contain trustworthy additional particulars," such as the statement that Paul taught in the lecture-room of Tyrannus "from the fifth to the tenth hour" (added to Acts 19:9). In his later work, St Paul the Traveller and the Roman Citizen (1895), Ramsay's views gain both in precision and in breadth. The gain lies chiefly in seeing beyond the Bezan text to the "Western" text as a whole.

Structure and content[edit]

Structure[edit]

Acts has two key structural principles. The first is the geographic movement from Jerusalem, centre of God's Covenantal people the Jews, to Rome, centre of the Gentile world. This structure reaches back to the author's preceding work, theGospel of Luke, and is signaled by parallel scenes such as Paul's utterance in Acts 19:21, which echoes Jesus' words 9:51 (Paul has Rome as his destination, as Jesus had Jerusalem). The second key element is the roles of Peter and Paul, the first representing the Jewish Christian church, the second the mission to the Gentiles.[31]

- Transition: reprise of the preface addressed to Theophilus and the closing events of the gospel (Acts 1-1:26)

- Petrine Christianity: the Jewish church from Jerusalem to Antioch (Acts 2:1-12:25)

- 2:1-8:1 - beginnings in Jerusalem

- 8:2-40 - the church expands to Samaria and beyond

- 9:1-31 - conversion of Paul

- 9:32-12:25 - the conversion of Cornelius, and the formation of the Antioch church

- Pauline Christianity: the Gentile mission from Antioch to Rome (Acts 13:1-28:21)

- 13:1-14:28 - the Gentile mission is promoted from Antioch

- 15:1-35 - the Gentile mission is confirmed in Jerusalem

- 5:36-28:31 - the Gentile mission, climaxing in Paul's passion story in Rome (21:17-28:31)

Outline[edit]

|

|

Content[edit]

The gospel of Luke began with a prologue addressed to an individual by the name of Theophilus (though this name, which translates literally as "God-lover"; Acts likewise opens with a prologue and refers to "my earlier book", almost certainly the gospel.

The apostles and other followers of Jesus meet and elect Matthias to replace Judas as a member of The Twelve. On Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends and confers God's power on them, and Peter, along with John, preaches to many in Jerusalem, and performs Christ-like healings, casting out of evil spirits, and raising of the dead. At first many Jews follow Christ and are baptized, but the Christians begin to be increasingly persecuted by the Jews. Stephen is arrested for blasphemy, and after a trial, is found guilty and stoned by the Jews, becoming the first Christian martyr.

The church continues to grow, and begins to spread to the Gentiles. Peter has a vision in which a voice commands him to eat a variety of impure animals, saying, "Do not call anything impure that God has made clean." Peter awakes from his vision and meets with Cornelius the Centurion, who becomes a follower of Christ.

Saul of Tarsus, a Jew who persecutes the Christians, has a vision of the risen Christ on the road to Damascus and hears a voice saying, "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?" Saul, his name now changed to Paul, travels to Jerusalem where he meets with the apostles (the Council of Jerusalem). The apostles of the Jerusalem church have been preaching that circumcision is required for salvation, but Paul and his followers strongly disagree. After much discussion, James the Just, leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile Christian converts need not follow all of the Mosaic Law, and in particular, do not need to be circumcised.

Paul spends the next few years traveling through western Asia Minor and the Aegean,preaching, converting Gentiles, and founding new churches. On a visit to Jerusalem he is set on by a Jewish mob. Saved by the Roman commander, he is accused by the Jews accused of being a revolutionary, the "ringleader of the sect of the Nazarenes", and imprisoned. Paul asserts his right as a Roman citizen, to be tried in Rome and is sent by sea to Rome, where he spends another two years under house arrest, proclaiming the Kingdom of God and teaching the "Lord Jesus Christ". Acts ends abruptly without recording the outcome of Paul's legal troubles.

Theology[edit]

Attention to the oppressed and persecuted[edit]

The Gospel of Luke and Acts both devote a great deal of attention to the oppressed and downtrodden. The impoverished are generally honored. A great deal of attention is devoted to women in general,[32] and to widows in particular.[33] The Samaritans of Samaria had their temple on Mount Gerizim, placing them at odds with Jews of Judea, Galilee and other regions who had their Temple in Jerusalem and practised Judaism. Unexpectedly, since Jesus was a Jewish Galilean, the Samaritans are shown favorably in Luke-Acts.[34] In Acts, attention is given to the religious persecution of the early Christians, as in the case of Stephen's martyrdom and the numerous examples are Paul's persecution for his preaching of Christianity.

Prayer[edit]

Prayer is a major motif in both the Gospel of Luke and Acts. Both books have a more prominent attention to prayer than is found in the other gospels.[35] The Gospel of Luke depicts prayer as a certain feature in Jesus's life. Examples of prayer which are unique to Luke include Jesus's prayers at the time of his baptism (Luke 3:21), his praying all night before choosing the twelve (Luke 6:12), and praying for the transfiguration (Luke 9:28). Acts also features an emphasis on prayer and includes a number of notable prayers such as the Believers' Prayer (4:23–31), Stephen's death prayer (7:59–60), and Simon Magus' prayer request (8:24). See also Prayer in the New Testament.

Comparison with other writings[edit]

Pauline epistles: Historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles[edit]

Modern scholarship has rejected the proposal that the author of Acts was Luke the companion of Paul, a contemporary of the events the book describes and an eyewitness to many of them.[1] The book originally appeared anonymously, the traditional attribution began only in the late 2nd century, and the use of medical terms, claimed in the 19th century as evidence of authorship by a physician, (as Luke is said by to be in Colossians 4:14) ), is no more than was common among educated people of the time.[36] The strongest evidence of Lukan authorship is the "we" passages, but other explanations of these are more probable.[36]

Speeches: Luke-Acts and Hellenistic historiography[edit]

Acts features twenty-four extended speeches or sermons from Peter, Paul, and others. The speeches comprise about 30% of the total verses.[37] These speeches, which are given in full, have been the source of debates over the historical accuracy of Acts. Some scholars have objected to the language of the speeches as too Lukan in style to reflect anyone else's words. George Shillington writes that the author of Acts most likely created the speeches and accordingly they bear his literary and theological marks.[38] Conversely, Howard Marshall writes that the speeches were not entirely the inventions of the author and, while they may not be verbatim, nevertheless they record the general idea. He compares this to the work of the historian Thucydides, who found it difficult recording speeches verbatim but instead had the speakers say what he felt was appropriate for them to say on the occasion while adhering as much as possible to the general sense.[39]

使徒行傳

| 書的新約 |

|---|

|

| 福音 |

| 馬修 · 馬克 · 盧克 · 約翰 |

| 使徒行傳 |

| 使徒行傳 |

| 書信 |

| 羅馬書 哥林多前書 · 哥林多後書 加拉太書 · 以弗所書 腓立比書 · 歌羅西書 帖撒羅尼迦前書 · 帖撒羅尼迦後書 提摩太前書 · 提摩太後書 提多 · 腓利門書 希伯來書 · 詹姆斯· 彼得 · 彼得後書 約翰 · 約翰二書 · 約翰三書 猶大書 |

| 啟示 |

| 啟示 |

| 新約聖經手稿 |

在使徒行傳(古希臘:ΠράξειςτῶνἈποστόλων,Práxeis噸Apostólōn ; 拉丁語:ACTUSApostolōrum),常簡稱為徒,是第五本書新約聖經 ; 使徒行傳勾勒出的歷史使徒時代。

使徒行傳講述了早期基督教教堂的故事,特別強調了部使徒 西門彼得和大數的保羅,誰是這本書的中間和後面的章節中的核心人物。早期的章節,在設置耶路撒冷,討論耶穌的復活,他的升天,在五旬節和使徒開始的事工。在後面的章節中討論保羅的轉換,他的事工,最後他被逮捕,監禁,並前往羅馬。這本書的一個重要主題是擴大聖靈的工作從猶太人,圍繞在耶路撒冷,到外邦人在整個羅馬帝國。

這幾乎是普遍一致認為,使徒行傳的作者也寫了盧克的福音,但現代學者已經拒絕傳統,路加-使徒行傳的作者路加是保羅的同伴,一個當代的書中描述了事件和目擊者來許多人。[ 1 ]

組成和設置[ 編輯]

[ 編輯]

標題(“使徒行傳” 希臘 Πράξειςἀποστόλων Praxeis Apostolon)最早是由愛任紐後期公元2世紀。目前還不知道這是否是由愛任紐發明了一種現有業權或1; 然而,它似乎清楚,它不是由作者給出。[ 2 ]

路加福音和使徒行傳的福音做了兩卷本作品的學者叫路加-使徒行傳。[ 3 ]他們一起佔27.5%,新約聖經,由單一作者的貢獻最大,為這兩個教會的禮儀框架日曆和成後人都裝有耶穌的故事和早期教會他們的想法的歷史輪廓。[ 4 ]

,作者是不是在任一音量命名為[ 5 ]根據教會的傳統可以追溯到公元2世紀,他是“路加福音”命名為一個同伴使徒保羅在三個歸因於保羅自己的信件; 這種觀點仍然是有時先進,但“關鍵共識強調在使徒行傳和正宗的保祿書信的帳戶之間的無數矛盾。”[ 6 ](一個例子可以通過比較保羅的轉換行為的帳戶可以看出(使徒行傳9:1 -31,22:6-21,並26:9-23)與保羅自己的說法,他在猶太該事件發生後仍然不明的基督徒(加拉太書1:17-24)。)[ 7 ]他欣賞保羅,但他神學是對重點顯著不同於保羅和他沒有(使徒行傳)表示保羅的意見準確。[ 8 ]他被教育,一個人的方式,可能是城市,和別人誰尊重體力勞動,雖然不是勞動者本人; 這是顯著的,因為時間更達官顯貴作家看不起的工匠和小型企業的人誰做了保羅的早期教會和人想必盧克的觀眾。[ 9 ]

大多數專家至今的盧克-行為80-90 CE組成,雖然有些建議90-110。[ 10 ]傳統的歸屬地盧克保羅的同伴的日食意味著,早日為福音是現在很少提出來的。[ 6 ]有證據表明,這兩個文本(西方和亞歷山大的手稿家庭之間的衝突),並從馬吉安爭議(馬吉安是誰製作了他自己版本的基督教經文的基礎上路加福音和保羅的書信第2個世紀的異教徒)路加-使徒行傳仍然被大幅修改順利進入第2個世紀。[ 11 ]

類型和來源[ 編輯]

路加福音-使徒行傳的作者改編通史體裁不拘一格成小說文學作品缺乏確切的經典比喻。[ 12 ]他描述他的書為“敘事”(diegesis),而不是作為一個福音,並且含蓄地批評他的前輩不給他們的讀者耶穌和使徒的標記或一個“全”的報告,以及手段的發言,通過它古老的歷史學家轉達他們的敘述的意義。[ 13 ]

盧克,作為作者可以被稱為為方便起見,似乎已經為他的模型中的兩個推崇古典作家的作品,哈利卡那蘇斯的狄奧尼修斯,誰寫羅馬的歷史,以及猶太歷史學家約瑟夫,一個作者的猶太人歷史,[ 13 ]這三個錨各自人民的約會由創始人(羅穆盧斯,摩西和耶穌)的誕生和敘述的創辦人從神胞胎的故事,讓他們都是神的兒子的歷史。[ 13 ]每個創始人教權威性,似乎證人去世後,和升天。[ 13 ]這三個方面窮人和富人的“老外”是否要接收到人的問題之間的關係教學的重要方面。[ 13 ]

對於他的福音路加把他的源馬克福音,叫熟語集合Q源,和獨特的材料的集合稱為L(盧克)來源(“獨一無二”的意思是僅見於路加)。[ 14 ]的來源使徒行傳的那麼肯定。馬克仍然使用在一定程度上,通過轉事件,馬克在耶穌使徒的時間生活-例如,關於在馬可福音7“清潔”和“不潔”的材料是用在使徒行傳10,和馬克的帳戶的指責耶穌已經襲擊了廟(馬克14點58分)是用來在使徒行傳中司提反(使徒行傳14分)。故事[ 15 ]總的來說,然而,使徒行傳的來源只能是在猜測根據內部證據:三個“我們”的段落,例如,可能指向這樣一個源,與傳統的解釋是,他們所代表的目擊者帳戶。[ 16 ]另外可能的來源可能包括其他各種旅遊賬目,在第1-5章早年耶路撒冷教會的(可能是兩個這樣的人士透露,“耶路撒冷A”和“耶路撒冷B”,如一些敘述出現兩次),掃羅的轉換的故事,並在故事的故事“彼得使徒行傳” -這個列表並不詳盡,並沒有一定的。[ 17 ]

[ 編輯]

盧克被寫入朗讀一組耶穌追隨者聚集在一所房子,分享主的晚餐。[ 13 ]筆者假設一個受過教育的英語為母語的受眾,但引導他注意具體基督徒的關注,而不是對希臘羅馬世界。[ 18 ]他開始他的福音與前言寫給“提阿非羅”,通知他打算向他提供了一個“有序的帳戶”活動,將帶領他的讀者“的確定性。的[ 9 ]他做了不寫文章是為了提供提阿與歷史的理由- “會發生?” -而是鼓勵信仰- “?發生了什麼事,什麼所有這一切意味著” [ 19 ]

使徒行傳(或路加-使徒行傳)是一個旨在作為一個工作“的熏陶。” [ 20 ]教化的意思是“經驗性論證美德優於惡習,” [ 21 ],但不是所有的盧克的目的。他還從事與基督教與羅馬帝國,這一天民間力量適當關係的問題:可能是基督徒順服上帝,也撒?答案是模棱兩可的。[ 22 ]羅馬人從來沒有反對耶穌或他的追隨者移動,除非挑起的猶太人,在審判的場面基督教傳教士總是被清零的違反羅馬法律的指控,和使徒行傳與保羅結束在羅馬宣布基督教在羅馬保護的消息; 與此同時,盧克明確指出,羅馬人,像所有塵世統治者,接受他們的權力來自撒旦,而基督是統治者神的國。[ 23 ]

路加-使徒行傳也可以看作是(或“道歉”)的耶穌運動的防禦給猶太人:大頭在使徒行傳的演講和布道是針對猶太人的觀眾,與羅馬人具有外部仲裁者的糾紛。關於猶太人的習俗與法律[ 22 ]一方面,盧克刻畫基督徒猶太人的教派,因此有權獲得法律的保護作為一個公認的宗教; 另一方面,盧克似乎不清楚未來上帝要猶太人和基督徒慶祝耶穌和他的直接追隨者的猶太同時強調如何猶太人拒絕了上帝的應許的彌賽亞。[ 24 ]

手稿[ 編輯]

最早的手稿證人路加福音(技術術語的書面資料)五三世紀的紙莎草紙碎片; 最早的完整的認證工作是第4個和第5個世紀。[ 25 ]這分為兩個“家庭”,西部和亞歷山大:這之間的差異造成重大困難,而“原”文字的問題仍然沒有得到解決。[ 26 ]佔主導地位的觀點是,西方的文字表示有意修改或編輯,作為變化似乎形成特定的模式。[ 27 ] [注1 ]

最喜歡的聖經書,還有使徒行傳中現存最早的手稿之間的差異。這是因為有三個不同的家庭聖經的文本,拜占庭式,西式和亞歷山大。從西文字型(由表示的手稿法典bezae食品)和亞歷山大文本型(由代表西奈抄本)是最早的倖存者。行為在西方手稿保存下來的版本包含了比使徒行傳的亞歷山大版本約10%的內容。有些學者一直在努力,以確定是否這兩種版本的更接近由原作者組成的原始文本。在拜占庭式的文字家庭,一個清晰的正版閱讀出現在整個新約聖經通過比較不同的手稿。

早期的理論,由瑞士神學家提出讓勒克萊爾在17世紀,斷定,較長的西方版本是第一稿,而亞歷山大的版本代表了更精緻的修訂由同一作者。這一理論的擁護者認為,即使在兩個版本分歧,它們都具有相似性在詞彙和寫作風格,這表明兩個共享一個共同作者。然而,有人認為,如果兩個文本寫由同一人,他 們應該有完全相同的神學,他們應該同意對歷史問題。由於一些現代學者做檢測文本之間微妙的神學和歷史的差異,這樣的學者,不同意的rough-draft/polished-draft理論。

第二種理論涉及的拜占庭式的文本類型。該系列還包括現存的手稿可以追溯到公元5世紀或更高版本; 然而,紙莎草紙碎片可以用來表明該文本類型的,早在亞歷山大還是西方文字類型的日期。[ 28 ]許多人認為這組文本通過看拜占庭式文本來自使徒行傳書正本整個新約。他們認為,這個文本家族最古老的副本可能已遺失或毀壞隨著時間的使用,因此,現存的手稿不能準確地約會一個文本的家庭。大部份的聖經手稿的支持拜占庭家庭,從中單一的閱讀新約的建立。拜占庭文本類型被用於16世紀的Web網站receptus,新約聖經的一個希臘語言版本的印刷機進行印刷。該Web網站receptus,反過來,用於在英語語言中發現的新約全書國王詹姆斯聖經。今天,拜占庭文本型是新的興趣從發現的這些西方和亞歷山大文本類型文本的原始形式的主題。[ 29 ]

第三個理論假設西部和亞歷山大文本的共同作者,但聲稱亞歷山大文字是短初稿,與西方文字是一個較長的拋光草案。

第四個理論是,較長的西方文字來第一次,但後來,其他一些纂或縮寫的一些材料,導致較短的亞歷山大文本。

到了近代,還有另一種理論認為,有一部分是贊同。根據這一新的理論,在較短的亞歷山大文本更接近原始的,和更長的西方文字是後來插入的額外材料到文本的結果。[ 30 ]在1893年,爵士WM拉姆齊在教會的羅馬帝國認為,食品法典委員會bezae食品(西文)擱在一個校訂在做小亞細亞(介於以弗所和南部加拉太),不晚於約公元2世紀中葉。一些人認為,修訂中的問題是一個單一的審校,誰在他的修改和補充表示,當地在解釋他自己的時間投入在使徒行傳的工作。他的目的,在西裝的文字他那個時代的觀點,部分是使其更易於理解公眾,一方面也使之更加完整。為此,他補充說:“一些觸及到的地方倖存的傳統似乎包含守信額外的細節,”比如,保羅教導“從第五到第十小時的”演講室推喇奴的聲明(添加到使徒行傳19:9) 。在他的後期作品,聖保羅的旅行者和羅馬公民(1895年),拉姆齊的意見精度和廣度兩個增益。收益主要在於在看到超越Bezan文字的“西方”的文本作為一個整體。

結構和內容[ 編輯]

結構[ 編輯]

徒有兩個關鍵的結構原則。首先是地理運動從耶路撒冷,上帝的聖約人是猶太人的中心,羅馬,外邦世界的中心。這種結構可以追溯到作者的前期工作中,盧克的福音,並通過並行的場景,如保羅的話語在使徒行傳19:21,這呼應了耶穌的話暗示9:51(保羅羅馬作為他的目標,因為耶穌耶路撒冷)。第二個關鍵因素是彼得和保羅的第二個使命,以外邦人的角色,第一次代表猶太基督教教堂,。[ 31 ]

- 過渡:再發生的前言寫給提阿和福音的收事件(使徒行傳1-1:26)

- 伯多祿基督教:猶太教教會從耶路撒冷到安提阿(徒2:1-12:25)

- 2:1-8:1 - 在耶路撒冷開始

- 8:2-40 - 教會擴展到撒瑪利亞和超越

- 9:1-31 - 保羅的

- 9:32-12:25 - 科尼利厄斯的轉換,並安提阿教會的形成

- 寶蓮基督教:外邦人的使命從安提阿到羅馬(徒13:1-28:21)

- 13:1-14:28 - 外邦人的使命是從安提阿推廣

- 15:1-35 - 外邦人的使命是確定在耶路撒冷

- 5:36-28:31 - 外邦人的使命,達到高潮在羅馬(21:17-28:31)保羅的激情故事

概要[ 編輯]

|

|

內容[ 編輯]

在盧克的福音一開始的序幕由提阿的名字給一個人(儘管這個名字,字面翻譯為“神的情人”;徒也打開了序幕,指的是“我以前的書”,幾乎可以肯定的福音。

耶穌的使徒和其他追隨者見面,選出馬提亞,取代猶大為十二的成員。在五旬節時,聖靈降臨,並賦予神的力量在他們身上,彼得,一起約翰,鼓吹許多在耶路撒冷,並執行基督般的醫治,趕鬼的,和死者飼養。起初,許多猶太人跟隨基督並受洗,但基督徒開始被越來越多地迫害猶太人。斯蒂芬是涉嫌褻瀆和審判後,被發現有罪,並投擲石塊的猶太人,成為第一個基督教殉道者。

教會繼續增長,並開始蔓延到外邦人。彼得有一個設想,其中一個聲音命令他吃各種不潔的動物,說:“不要當作俗物,神所潔淨的。” 彼得醒悟從他的遠見和會見百夫長哥尼流,誰成為基督的追隨者。

大數,一個猶太人誰迫害基督徒的掃羅有復活的基督在前往大馬士革的路上的景象,聽到一個聲音說:“掃羅,掃羅,你為什麼逼迫我?” 掃羅,他的名字現在改為保羅前往耶路撒冷在那裡他遇見了使徒(在耶路撒冷的會議)。耶路撒冷教會的使徒一直鼓吹割禮是必需的救贖,但保羅和他的追隨者強烈反對。經過多次討論後,詹姆斯剛,耶路撒冷教會的領袖,法令,外邦基督徒的轉換不需要遵循所有的鑲嵌法,特別是,不需要受割禮。

保羅花未來幾年通過小亞細亞西部和愛琴海旅遊,說教,轉換外邦人和創辦新的教會。在訪問耶路撒冷,他被設置在一個猶太暴民。由羅馬統帥保存,他被指控為一個猶太人指責革命性的“魁首的拿撒勒教的”,和囚禁。保羅聲稱他的權利,一個羅馬公民,在羅馬受審,是由海發往羅馬,在那裡他度過了兩年軟禁,宣講神的國和教學的“主耶穌基督”。徒突然結束沒有記錄保羅的法律糾紛的結果。

神學[ 編輯]

注意壓迫和迫害[ 編輯]

路加福音和使徒行傳雙方投入了極大的關注被壓迫和被踐踏。貧困是普遍尊敬。一個很大的注意力投向女性在一般情況下,[ 32 ],並在特定的寡婦。[ 33 ]的撒瑪利亞人的撒瑪利亞有他們在寺廟基利心山,將它們放置在賠率與猶太人猶太,加利利和誰過其他地區他們在耶路撒冷聖殿和實踐猶太教。沒想到,因為耶穌是一個猶太加利利,撒瑪利亞人都毫不遜色所示路加-使徒行傳。[ 34 ]在使徒行傳,注意了早期基督徒的宗教迫害,因為在斯蒂芬的殉難和無數的例子的情況下,是保羅的迫害他的基督教講道。

祈禱[ 編輯]

禱告是在路加福音雙方的福音和行為的主要動機。這兩本書有一個更突出的要專心以祈禱比在其他福音書找到。[ 35 ]路加福音描繪的禱告在耶穌的生活有一定的功能。禱告都有它獨特的盧克例子包括耶穌的在他受洗時禱告(路加3點21分),他的祈禱整夜選擇12前(路6:12),和祈禱的變身(路加福音9時28分) 。使徒行傳還設有一個注重禱告,包括許多著名的祈禱如的信徒的禱告(4:23-31),斯蒂芬的死禱告(7:59-60),和西蒙法師的禱告請求(8:24) 。又見祈禱在新約。

與其他著作比較[ 編輯]

保羅書信:的使徒行傳歷史的可靠性[ 編輯]

現代學者已經拒絕了使徒行傳的作者路加是保羅,一個當代的書中描述了事件和現場目擊者向他們中許多人的同伴的建議。[ 1 ]這本書最初出現匿名的,傳統的歸屬才開始在晚2世紀,並使用醫療術語,聲稱在19世紀作為作者的由醫生證明,(盧克是要在歌羅西書4:14說)),不超過是受過教育的人之間的共同的時間。[ 36 ] Lukan作者的最有力的證據是“我們”的段落,但這些其他解釋的可能性更大。[ 36 ]

演講:路加-使徒行傳和古希臘史學[ 編輯]

使徒行傳功能24從彼得,保羅和其他擴展的演講或說教。發言包括約30%的總詩句。[ 37 ]這些演講,這完全是給定的,已經在使徒行傳的歷史準確性一直爭論的來源。有學者反對風格的發言太Lukan的語言來反映別人的話。喬治·希林頓寫道,作者的行為最有可能創建的發言,因此他們承擔他的文學和神學的痕跡。[ 38 ]相反,霍華德·馬歇爾寫道,發表講話時都沒有的作者完全的發明,雖然他們可能不是逐字,但他們錄製的總體思路。他比較這對歷史學家的工作,修昔底德,誰發現很難錄音講話逐字而是有喇叭說什麼他感覺是適合他們說之際,同時堅持盡可能以一般意義上的。

留言列表

留言列表

{{ article.title }}

{{ article.title }}